Antibodies in Sanfilippo Children May Jeopardize Effectiveness of Gene Therapies, Study Finds

High numbers of antibodies targeting different types of adeno-associated viruses (AAV) pose challenges for AAV-based gene therapies in Sanfilippo syndrome children, according to researchers.

The study, “Differential prevalence of antibodies against adeno-associated virus in healthy children and patients with mucopolysaccharidosis III: perspective for AAV-mediated gene therapy,” was published in the journal Human Gene Therapy Clinical Development.

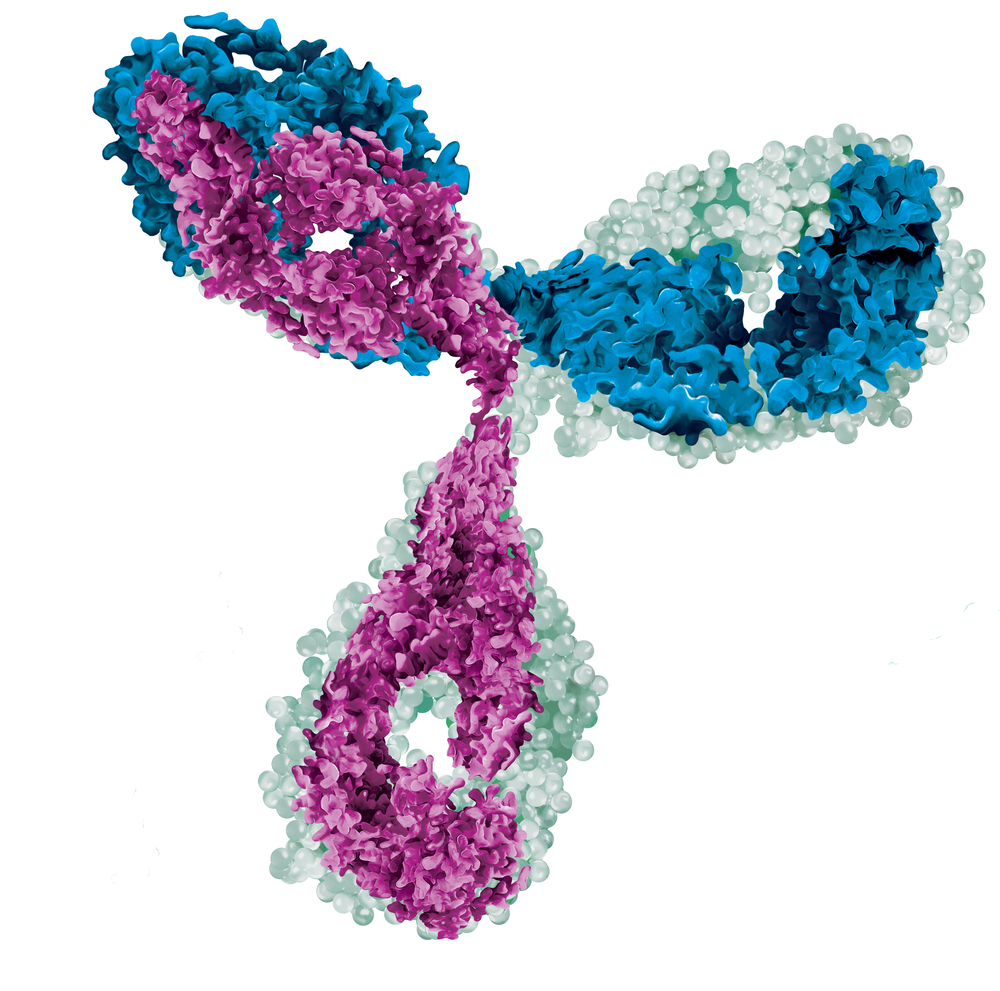

Promising gene therapies for Sanfilippo syndrome use the recombinant adeno-associated virus (rAAV) as a vehicle to deliver compounds into patients’ cells.

Posing no harm and widespread in humans, more than 90% of adults carry antibodies against AAV. But the presence of these antibodies means they can severely impair the efficacy of rAAV gene therapies.

Researchers from The Ohio State University and Nationwide Children’s Hospital, both in Columbus, Ohio, analyzed blood samples from 38 children with Sanfilippo syndrome (also known as mucopolysaccharidosis III), 24 with the disease subtype A and 14 with the subtype B, to evaluate the proportion of children with antibodies directed against AAV.

Blood samples from 35 healthy children were used as controls.

The levels of antibodies were assessed against different variables (seroptypes) of AAVs — from serotype 1 to 9 and an additional one called rh74 — in both groups of disease subtype groups.

Sanfilippo syndrome and healthy children were found to have a similar prevalence of all different AAV serotypes. But children with Sanfilippo syndrome between 2 and 8 years old carried higher levels of antibodies against the majority of serotypes, especially αAAV1 and αAAVrh74, compared to healthy children.

“Disease pathologies or patient environment may increase exposure or trigger susceptibility to AAV infections,” researchers wrote.

Most AAV serotypes (except AAV8 and AAV9) in Sanfilippo syndrome children peaked until the age of 8. In contrast, there was a significant increase in seroprevalence for the majority of AAV serotypes tested between the ages of 8 and 15 in healthy children.

The lower prevalence of antibodies against AAV in Sanfilippo syndrome children after the age of 8 may be the linked to “reduced exposure to AAV, due to limited social interactions due to severe progressive neurodegeneration,” the research team wrote.

Antibodies targeting AAVrh74 were present at higher levels than those targeting other AAV types, with an incidence of 51% to 75% among all groups before the age of 8 and persisting beyond age 8 in the Sanfilippo group.

AAVrh74 has recently been shown to have the capacity of crossing the blood-brain barrier — a selective membrane that shields the central nervous system from the general blood circulation — in a mouse model of Sanfilippo syndrome, supporting its potential use for gene therapies.

However, “the high seroprevalence may hinder the potential of AAVrh74 as a gene therapy vector by systemic delivery for the treatment of MPS III [Sanfilippo syndrome] and other neurological disease in general,” according to the study.

Overall, this study highlights the challenges facing AAV-based therapies for Sanfilippo syndrome patients. New approaches to deplete these AAV-targeting antibodies are needed to effectively use promising AAV-based gene therapies in the future.